Learning SQL With Small Data Pt 2: Taking Apart a Many-to-Many Relationship

If you haven’t yet, read part 1 of this two part series on SQL concepts which goes over setting up the database used in following examples. It also introduces querying relational data concepts through simple JOIN and subquery counting examples.

We’ll continue working with the fake library data we’ve been using, but now we’ll focus on a couple new tables that deal with the relationship between two entities: users and books. Users and books share a “many-to-many” relationship; users can have many books and books can have many users.

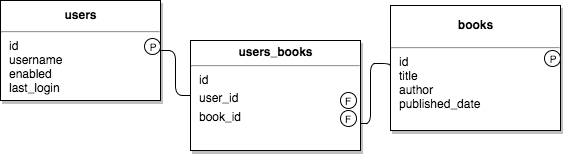

Although there are only two entities in our conceptual entity relation diagram (ERD), there are three tables that comprise this relationship at the database table level: users, books, and users_books. When working with a Many-to-Many relationship you set up a third table, known as the join table, which provides data on the relationship between the two main tables. The users_books join table could probably just as easily be named “checkouts”, which is a better descriptor for the relationship (and interaction) between users and books in this case.

The role of the two main tables is fairly simple; a row in the users table holds a user record and likewise for the books table. What does a users_books table row look like, though?

At minimum, a join table row (i.e. one “book checkout”) will need to include data that identifies one user and one book. A join table row does this by including at a minimum two columns: one column from each of the two main tables to serve as identifying keys. Because keys from one table now also reside on another table, they’re referred to as foreign keys. Here’s an entity relation diagram to help illustrate the relationship we just described between the users and books tables. The letter P represents the primary keys and the letter F represents foreign keys.

SQL is a large topic, so it will be a bit easier to get started by identifying a specific question and then trying to answer it using SQL. Our first question will be, what are the checkouts that have happened at this library? The data for a book checkout should include the user’s name that checked out the book and the book’s title.

Here’s a query on a Many-to-Many relationship that’s similar to one found in the LaunchSchool book’s JOIN section.

SELECT users.username, books.title

FROM users

INNER JOIN users_books ON (users_books.user_id = users.id)

INNER JOIN books ON (books.id = users_books.book_id);

username | title

------------+--------------------

John Smith | My First SQL book

John Smith | My Second SQL book

Jane Smiley | My Second SQL book

When I first started working with JOINs I didn’t really understand how JOINs on Many-to-Many relations worked, so I tried switching the order of the JOINs to see what happened.

SELECT users.username, books.title

FROM users

INNER JOIN books ON (books.id = users_books.book_id) /* Switched order */

INNER JOIN users_books ON (users_books.user_id = users.id);

ERROR: missing FROM-clause entry for table "users_books"

LINE 3: INNER JOIN books ON (books.id = users_books.book_id)

Annnnnd I broke it.

When you break something and don’t know why, that’s a clear indication that you have some gaps in your knowledge. What helped me finally get a stronger grasp of how this type of JOIN worked was to use some of the tools we’ve been practicing: use a small set of data to display the data available to us and checking how this data can change.

So let’s start building up this query that broke, starting with one of the simplest statements we can execute.

/* Adding additional info to SELECT to show more data */

SELECT u.id, u.username

FROM users u

FROM users brings in the data displayed in our results.

id | username

----|-------------

1 | John Smith |

2 | Jane Smiley |

3 | Alice Munro |

Ok, now that we’ve got some users, we just need to query for books, right? Without considering how you query a Many-to-Many relation, you might indeed think this and go straight to writing a JOIN like this next.

INNER JOIN books ON (books.id = users_books.book_id)

Here’s the whole query so far.

SELECT u.id, u.username

FROM users u INNER JOIN books ON (books.id = users_books.book_id);

Let’s run it.

ERROR: missing FROM-clause entry for table "users_books"

LINE 3: INNER JOIN books ON (books.id = users_books.book_id)

Hmm, looks like we don’t have access to the users_books table. It’s hard to tell if we retrieved books rows in our result table in our last query since it threw an error, so let’s try another similar one.

SELECT u.id, u.username, books.title

FROM users u

INNER JOIN books ON (books.id IS NOT NULL);

id | username | title

----+-------------+--------------------

1 | John Smith | My First SQL book

2 | Jane Smiley | My First SQL book

3 | Alice Munro | My First SQL book

1 | John Smith | My Second SQL book

2 | Jane Smiley | My Second SQL book

3 | Alice Munro | My Second SQL book

1 | John Smith | My Third SQL book

This query is a little strange - rather than doing a traditional INNER JOIN it’s returning the Cartesian product of our two tables which is essentially what a CROSS JOIN does. The result itself isn’t very useful, but it does tells us something important:

1) The table referenced immediately after the JOIN command adds data to the results

Even though this query was strange, one observation we can make from it was that our JOIN added data from the books table to our results.

Thinking back to our original problem, our inability to access users_table tells us something else.

2) You can only utilize data already added to your results table

This is a really important point for working with queries that join more than one table. In terms of writing queries on Many-to-Many relations, this lets us know that we need to first retrieve results that provide a link between the users and books tables. Foreign keys link tables, and the relevant foreign keys reside on the JOIN table as user_id and book_id (see the ERD diagram above) in the users_books JOIN table. To make sure we can link the two main tables, let’s first write a JOIN between our users and user_books tables.

/* Updating SELECT to show additional data */

SELECT u.id, u.username, ub.user_id, ub.book_id

FROM users u

INNER JOIN users_books ub ON (ub.user_id = u.id);

The above query returns these results:

|id | username | user_id | book_id|

|----+-------------+---------+---------|

| 1 | John Smith | 1 | 1|

| 1 | John Smith | 1 | 2|

| 2 | Jane Smiley | 2 | 2|

Now that we have book ids in our results, we are able to query for data related to those books.

SELECT u.id, u.username, ub.user_id, ub.book_id, b.id AS book_table_id, b.title

FROM users u

INNER JOIN users_books ub ON (ub.user_id = u.id)

INNER JOIN books b ON (b.id = ub.book_id);

id | username | user_id | book_id | book_table_id | title |

----+-------------+---------+---------+---------+--------------------

| 1 | John Smith | 1 | 1 | 1 | My First SQL book |

| 1 | John Smith | 1 | 2 | 2 | My Second SQL book |

| 2 | Jane Smiley | 2 | 2 | 2 | My Second SQL book |

Here’s the full query below rather than the diff if that helps.

SELECT u.id, u.username, ub.user_id, ub.book_id, b.id AS book_id, b.title

FROM users u

INNER JOIN users_books ub ON (ub.user_id = u.id)

INNER JOIN books b ON (b.id = ub.book_id);

To clean up our results, we can make SELECT a bit more restrict:

SELECT u.username, b.title

Which gets you this:

| username | title |

|-------------|--------------------|

| John Smith | My First SQL Book |

| John Smith | My Second SQL Book |

| Jane Smiley | My Second SQL Book |

Hopefully the inner workings of JOINs on Many-to-Many relationships are a bit less opaque now.