6 Questions Towards a Better Understanding of the JS Event Object

1 A post about asking questions to get crystal clear™ about something, incidentally about event objects

1 A post about asking questions to get crystal clear™ about something, incidentally about event objects

I want to talk about the JavaScript event object in this post, but first I want to give it a bit of context so that it makes sense as something important to understand.

The early days

In the early days of the web, users navigated through web pages and applications rather slowly for a number of reasons, but in part it was because they were doing it one page refresh at a time. A new tool for working with the web - JavaScript - made a significant impact in terms of how fast web sites seemed to users. Some of this was perception, but other innovations caused true paradigm shifts in how we use the web today. We’ll be taking a look at how JavaScript made it possible users to access faster, more interactive web experiences, and in doing so how it changed web development forever.

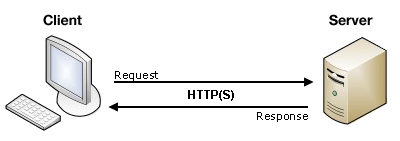

Here’s a brief description of what the process for using the web used to looked like this for visiting a static webpage: a user opens their browser, which we’ll refer to as the client, and click on a link or visits a URL. This initiates an HTTP GET request for a resource or document somewhere on the web. The server which hosts the resource or document is likely hundreds or thousands of miles away, and needs to send an HTTP response back to the client. Once this request is received, the document or resource will only become visible to the user after the response delivered new HTML to browser and it reloaded (refreshed) completely to rebuild the page. Needless to say, the unavoidable latency of HTTP and the need to constantly keep refreshing the page only made the web feel slow.

The first problem JS solved was additional page interactivity - you couldn’t do something as simple as change the color on a page before JavaScript.

See the Pen Change background color by Dylan (@dylankb) on CodePen.

Feel free to look at the source code of the snippet above, but in case you’re not familiar with JavaScript or JavScript events, we’ll be breaking down how this all works with examples later.

JavaScript had solved the problem of how to make the visuals of user interface feel more interactive for any webpage. Another trickier problem remained, though; working with web applications still felt very slow. Web applications use data, or state, to build up a page’s UI, but fetching and retrieving data on a server was still felt like a relatively slow process. As a web application user, if you did something like update a value in your web application you had to go through a similar process that we described for static websites - you had to wait for your page to refresh to see any changes or new information in your client.

Diagram of client-server architecture, where user interactions almost always required a full browser refresh to become visible2

If the ability to change page elements with clicks was a pretty big deal for websites, JavaScript events combined with the introduction XHR requests were a complete game changer for working with web applications. If a user wanted to interact with a web application, for example creating or updating a user profile, users could now asynchronously send data back to the server and update the DOM elements on the page with JavaScript. What this meant is that just because your application’s data changed you didn’t always need to go through a full request/response cycle and page reload to see the changes. This fundamental change in how users could interact with web sites and applications made JavaScript one of the most important programming languages for modern day web applications.

Just to make what we’re talking about a bit less nebulous, try comparing these two forms. The applications are each very smaller so they’re already relatively fast, but the first one should at least seem to be a bit faster.

To get into a bit more detail about what’s happening, the first form uses client-side JavaScript to submit data and inserts the new element in the DOM (page) using the jQuery library. The other requires visiting a new page and then going back to the original page before we can see our new any new data.

We went over how JavaScript affected some of the web’s history and development. This is a technical blog post, though, and while we looked at some examples of these changes we skipped over exactly how JavaScript made some of these changes possible. Although it’s impossible to explain everything about how JavaScript works on the web in one small blog post, I would like to talk about one point in particular: the JavaScript event object.

The main event

JavaScript leverages an interesting ability that helps it make web sites and applications feel more interactive - it “knows how to wait”. What I mean by that is, JavaScript application code on the browser usually needs to wait for something to transpire first before running, for example a user’s click. The most simple example we’ve seen so far has been clicking a button to have the background color change.

A key piece of the puzzle to allowing code to execute only when a specific event happens is the event object. An event object represents data related to how, what, and when an event in the browser occurred. When I ran into the concept of events, I wanted to be sure I was pretty clear on the principles that underly JavaScript’s ability to create, register, listen, and execute event-based code.

Below are some questions, and hopefully answers, that mirror some of the confusions I had when learning about JavaScript events. But first, let’s go over some facts about browser events.

Events - If only we listen, they will be heard

The browser and DOM are firing events all the time, regardless of what code we’ve written.

Besides obvious ones like a user clicking on the page, we also have things like the DOMContentLoaded event, which occurs when the DOM is parsed from HTML, and Window.onload, fires once all of the page’s assets are finished loading. However, apart from the fact that certain browser based events telling us things how well or quickly our application runs, they can’t influence how code our application runs until we listen for them.

Event-based code is the process of tying the execution of these events to code in our applications.

The Click Event: There and Back Again

So, let’s briefly overview what event implementation, capturing, bubbling are to make sure we’re on the same page.

Setting up an event listener

Elements, windows, documents and more all implement the EventTarget interface which allows developers to add EventListeners, often via the addEventListener method, which specifies an event type and a callback.

document.addEventListener('click',

function(e) { console.log('Clicked!', e) };

);

But you can also use global event handlers either in your JS or HTML if you apply it as an element attribute.

<button onclick="console.log('Clicked!', event)">

Click me

</button>

If the user clicks on the button element in the browser, then their console would receive an the contents of an event object back.

MouseEvent { currentTarget: null, target: div, type: 'click' }

The actual object contains more properties than I’ve listed above, but we won’t be covering those in this article. Also, don’t worry about the currentTarget here or why it’s null, we’ll go over why that is a little later.

If you’re curious about all the properties that are on the event object, you can open this Codepen and your browser’s developer tools to see the logged object in the Console tab.

Event DOM traversal & Propagation

I should also point out that an event traverses (moves across) the DOM when it dispatches, and there are certain rules which dictate this behavior.

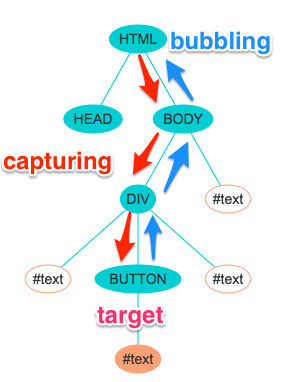

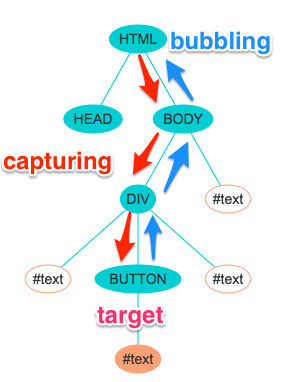

There are many overviews of DOM event traversal, but this one is mine.

When an element dispatches an event, all parent elements have the event fire in a capturing phase, the target fires in the target phase, and parent elements again fire in the bubbling phase. The listener by default only executes the event handler code in the target and bubbling stages.

This may seem a bit theoretical at this point, but I’ll be referencing this later on.

Now, on to the questions:

1) How exactly does the target property get set?

Here is the definition of the target property from the MDN documentation.

A reference to the object that dispatched the event

Ok, seems straightforward. You click on something and that’s the element which dispatches the event. This made me think of a slightly more complicated follow up question - if I add an event listener to a parent element and click on the inner child element, will the child element or the parent element dispatch the event?

A visual representation usually helps me, so I made the simplest one I could. In this example, there’s a div.button-container element, outlined in red, that contains a button.button element.

<div class="button-container">

<button class="button">Button</button>

</div>

I then attached an event listener to the div.button-container element once the DOM was loaded to fire a logger callback function.

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', function() {

document.querySelector('.button-container').addEventListener('click', logger);

});

In this case event listener is listening for the built-in click event and the logger function logs information on the event object - specifically what the target property is for each click event. Try clicking on both the button and div to see what happens.

See the Pen Bound container - target by Dylan (@dylankb) on CodePen.

You’ll notice that the target element changes depending on which of the two elements you click, regardless of whether it is nested or not.

If that seems like too simple of an explanation for you, I’ve got another one ;). In all seriousness, this may be a slightly less straightforward approach to thinking about how a target is set, but it actually was helpful in cementing my understanding.

What is a click? A possible alternative way about to think about target elements.

There is a description for the click event’s target property in the MDN documentation that doesn’t seem entirely accurate, but it did help me think about how the target property is actually determined.

The event target (the topmost target in the DOM tree).

To put this that into context, let’s look at some pictures first.

First, here’s the our containing div, highlighted by Chrome devtools:

Looking here, it clearly contains the button element nested inside it. Because it contains the button element, to click the button you have to effectively click on the div as well.

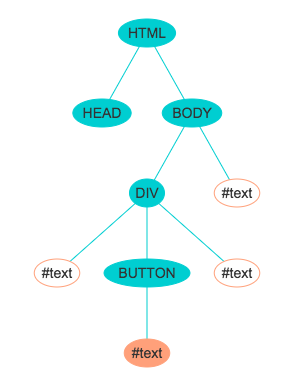

Here’s a DOM tree of our the markup in the previous code example:  3

3

Most representations of the DOM are “upside-down”, in that nested elements are the branches that extend downwards. So in this case, the button element is “lower” than the div.4 We can think about the div node pictured above as a starting a distinct “branch” of the DOM tree. It’s distinct in that containing elements lower down in the branch have a parent node (or element) with an attached event listener.

So, let’s review what we know.

- The event listener is attached to the parent

divelement - The

divcontains thebutton - Another way of saying that the

buttonelement is nested in thedivis to say that that thedivis higher in the DOM tree

Now pretend we have an element with an event listener attached to it. If the element with the event listener or any other element lower than it on the branch is clicked, these elements can set a target property on a new event object. So in this case, either the div or the button could set the target property.

If we click on button that’s inside of div, how do we know which on will set the target? If you click on an element, the most “specific” element relative to that click will be the one to set target. Another way of phrasing specific is to say, the “lowest” (i.e farthest from the root) element in a given DOM tree branch. If you click directly on the button, sure you clicked the div as well, but the most specific one is the button since it’s lower on the branch of elements you clicked on.

In summary, for a given click, whichever element was the “lowest” or “bottom-most” element in that DOM tree branch under the click will set the target property. This digression might be more confusing than helpful, but I thought that was an interesting way to think about something as simple as clicking something on a page :)

Dispatching events: Another target setting description

Another way of describing how the target property is determined is on this page comparing different event targets.

The DOM element on the left-hand side of the call that triggered this event, eg:

element.dispatchEvent(event)`

There may be some further implementation details that could help us determine which element calls the dispatchEvent, but that may be a bit too low level for the purposes of application development.

TLDR; In the example of the click event, the element you click on should reliably be the target property.

2) How does a child element dispatch an event to a parent listener?

We came to a nice simple conclusion above that the target property is basically whatever element you directly clicked on. But, how actually does the event object fire if you’re not directly clicking on the parent element?

Remember when I said that funny looking chart with arrows would be important, well that time has come. Here it is again.

So recall that all events:

- Travel up and down their DOM tree branch twice.

- The listener by default only executes the event handler code in the target and bubbling stages.

Now that we understand how traversal works and how the target property is set, we have the tools to understand how an event on a child element triggers a parent listener. If it isn’t clear yet, bubbling is a key player here.

Dispatched events will bubble up from child elements, and by default will trigger parent listeners. Therefore, a click on button will fire the event handler attached to div.button-container.

3) How do the target and currentTarget properties vary under different settings?

First, let’s look into how the currentTarget is determined. Here’s the definition from the docs:

… It always refers to the element to which the event handler has been attached, as opposed to

event.targetwhich identifies the element on which the event occurred.

Recall that our event listener is attached to the div. Given this fact and the above definition, we can probably guess what the current target will be, but a coded visual always helps:

See the Pen Bound container - targets by Dylan (@dylankb) on CodePen.

Whether we click on the button or the div, the currentTarget is always the div. That makes sense, as the div is “the element to which the event handler” has been attached.

Going back to the definition of currentTarget, here’s a preceding sentence that I left out earlier:

Identifies the current target for the event, as the event traverses the DOM.

We can actually confirm that currentTarget is transient in nature because of this previous log snippet we included in a of a simple click event attached to document

MouseEvent { currentTarget: null, target: div, type: 'click' }

Here we’d actually expect currentTarget to be document, right? Well, it is but logging an element returns a reference to an object, not the necessarily the values at the time of logging.

If we change the logging by copying the object values, we’ll actually get the value. If you want to see an example, open this Codepen and your developer tools to see the log.

Now that we know currentTarget changes during DOM travel, there’s more questions to ask…

4) What are the implications of event DOM traversal?

Ok, so with that in mind, let’s create a second additional separate event handler function called innerLogger. We will attach this listener to the nested button element.

document.querySelector('.button').addEventListener('click', innerLogger);

The functionality is entirely the same - all that’s different is it prepends “INNER” to all our previous output. Try clicking the two page elements in the results tab.

See the Pen Bound container - bubbling by Dylan (@dylankb) on CodePen.

Hmm, when clicking on button our output appears to be the same as before - it’s as if nothing seems to have changed.

What’s happened is we’ve created a subtle bug. If you were to insert a debugging statement or a console.log within innerLogger, you would see that the innerLogger event handler does indeed fire. The problem is that our logger event handler ALSO fires. In the first question we already confirmed that parent elements with event listeners will fire when the specified event occurs on their child elements. In this case, a button click bubbles up through each successive parent element until reaching the window element. The effect is that the output of innerLogger is replaced, or overwritten, by the output of logger.

In this case, stopping the continued propagation of the click event is the solution. We can stop the event from continuing to traverse (or propagate) across the DOM by commenting out line 2 in the Codepen. Once that’s done, we can now have separate logging behavior for the button and div click events.

In summary, one implication of DOM traversal is parent elements that share the same click event may fire. The reason that parent elements may fire after is due to bubbling. If we were using capturing, the result would be the parent elements or “top” elements would fire first.

5) Is this equal to currentTarget or target inside event handler callback functions?

The answer is by default - sometimes both, but almost always this is the same as currentTarget.

Let’s talk about why this is. This page contains the first explanation on how the this binding is set.

When the event handler is invoked, the

thiskeyword inside the handler is set to the DOM element on which the handler is registered.

The explanation is fairly understandable; this will be set to the element with the attached event listener. When using default bubbling, sometimes the element with the attached listener also dispatches the event to become the target (i.e clicking on the container div), and sometimes a nested element dispatches the event (i.e the button). That’s why the answer is “sometimes both”.

Let’s log out the this context to confirm our understanding.

See the Pen Bound container - this by Dylan (@dylankb) on CodePen.

Confirmed. In this case, the event listener was attached to the div. Therefore within the callback, div is both the currentTarget and the this context.

With all that said, the provided explanation may be slightly superficial, but we’ll revisit why in just a bit.

6) Does event delegation affect event object properties and context differently?

Event delegation lets you avoid adding individual event listeners to each element, and instead control which child events fire through attaching an event listener to a parent and adding additional code.

We could change our code to take advantage of event delegation through making changes like:

- Attaching our event listener to the

document, and avoid theDOMContentLoadedevent to fire - Add additional nested elements inside the

button-containerand have them not fire event listeners, behave differently, or whatever we want.

We’re not going to make those changes right now. Instead, we’ll do a somewhat contrived, but very simple, implementation of event delegation. We’ll wrap our logger code in a small conditional.

function logger() {

if (e.target.tagName === "BUTTON") {

// Leave existing logger code

}

The main body of our logger code will now only fire when the button is clicked, and not when the outer button-container is clicked.

See the Pen Bound container - delegation by Dylan (@dylankb) on CodePen.

As you can see, the other event properties are exactly the same as before event delegation. The currentTarget is still the div, the target remains button when clicking on the button, etc.

The story is a bit different with jQuery, however.

Understanding jQuery delegation principles

First, I want to go back to an issue I said I had about an excerpt from the this binding documentation. The excerpt says this is “… set to the DOM element on which the handler is registered”, which works fine for plain JavaScript. However, I prefer this definition from a different part of the MDN docs covering this.

When a function is used as an event handler, its this is set to the element the event fired from

The reason why is that in jQuery the on method allows for an optional selector parameter.

$('.button-container').on('click', '.button', logger);

Using jQuery parlance, up to now we’ve been directly binding elements (event targets) to their event listeners. Delegated events in jQuery have slightly different rules, as explained here

The handler is not called when the event occurs directly on the bound element, but only for descendants (inner elements) that match the selector.

To see the implications, click on the button below:

See the Pen Delegated container - jQuery by Dylan (@dylankb) on CodePen.

Events are still attached to div, however, the currentTarget and this context are now both button. To rephrase the jQuery documentation above, this is because if a selector is provided, the event occurs not on the element the event listener was added to, but on the element(s) matching the selector within the parent. With our additional selector of .button, elements matching the selector are now the ones that call event listeners, and NOT the parent with the attached event.

Further reading:

-

Screenshot taken using https://dom-viewer.herokuapp.com/ ↩

-

“Top” or “above” usually means “toward the “root” ↩